Vol. 46, Issue 1 ‣ profile

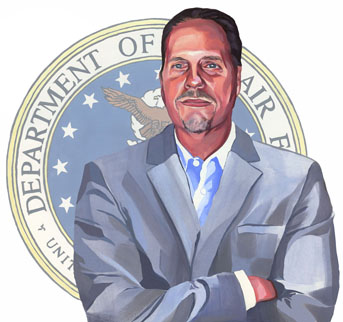

Former Air Force Officer Chuck Ruby

During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, tens of thousands of military personnel have received “mental illness” labels followed by prescriptions for brain-damaging psychiatric drugs.

But a growing number of mental health professionals, physicians and others now recognize the potential for grave harm inherent in the mass drugging of soldiers and veterans. “Over the last few years we have witnessed a rash of news reports of unusually high suicide rates, sudden cardiac deaths, and acts of violence committed by those who have been prescribed these chemical cocktails,” reported the International Society for Ethical Psychology & Psychiatry (ISEPP), a nonprofit with roots extending to the 1970s.

Late in 2012, according to Dr. Chuck Ruby, a clinical psychologist and chairman of ISEPP’s board of directors, the group launched Operation Speak Up to unify ISEPP’s efforts to help veterans and to change the federal government’s policy that relies heavily on drugs for treatment.

“At present, the government’s first line of treatment is the prescription of dangerous psychiatric drugs that are ineffective at best and deadly at worst,” said Ruby, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel whose 20-year military career included work as a counterintelligence special agent and investigative psychologist.

“This harm includes the typical ‘side effects’ that cause serious health problems, chemical insults to the brain and its functioning, and a dampening of important emotional signals that result in an ‘I don’t care’ attitude among those taking these drugs. This last problem can diminish concern for the consequences of one’s actions and increase the risk of impulsive and reckless behavior.”

According to Ruby, drug treatment for veterans stems from the erroneous concept that post-traumatic reactions are symptoms of a “disease” called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that must be medicated. “In reality, though,” he said, “there is nothing abnormal about such reactions to war.”

“It’s all just about being human,” Ruby told Freedom. “We have emotions in our human makeup. Those emotions are very functional and they are speaking to us when they happen. So when one is sad, sadness isn’t the problem. Sadness is a signal telling one there’s a loss somewhere in life and it is important to take a look at it.”

Contrary to media portrayals, veterans with war trauma aren’t “sick”—they are “reacting normally to abnormal experiences,” Ruby believes. Instead of handing them drugs, effective means must be made available to assist veterans, he said. “We want to give them a voice through talk therapies, peer counseling, and community support,” he said, methods that have been shown to help.

“The things that we refer to as ‘mental disorders’ aren’t truly real illnesses or any kind of neurological defect of the brain, so it doesn’t make sense to use any kind of medication to correct that defect, since it’s not there,” Ruby explained. Psychiatric drugs numb the brain or, in the form of stimulants, excite it, but in either case the drug “does not deal with the issues that are happening—it just masks them.”

“Most people taking psychiatric drugs have never been told by the person prescribing them what the harms or potential harms are of the drugs and how they work,” he said.

“They are given the impression that the drugs correct something, similar to how insulin corrects a metabolic problem, or how a blood pressure medicine might correct blood pressure. And they are quite surprised when they find out that is not the case.”

One drug can have any number of ill effects, he noted, and when an individual takes several, “you can get some pretty nasty results.”

“Clearly, it’s a crap shoot,” he said. “Even with one drug being prescribed, we don’t really know what that drug is doing to the human body. If you look at what is referred to as the ‘mechanism of action’ for any psychiatric drug in the Physicians’ Desk Reference or online at drugs.com, for example, you’ll see that the mechanism of action typically is stated as ‘unknown.’”

A bill introduced in Congress in 2012 by Senator Patty Murray of Washington State, which ISEPP hoped would have encouraged the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs to decrease the use of psychiatric drugs, mobilized ISEPP and Ruby into forming Operation Speak Up. Such drugs “are not appropriate, not only because there’s no real illness that’s being medicated,” Ruby said, “but because there’s a host of negative effects or what are typically called ‘side effects.’ Actually they are the main effects of the drug, everything from medical problems to increased suicidal thinking, increased aggression, things like that.”

Through letters, visits to Congressional offices and officials within the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, the Internet and other means, ISEPP and Operation Speak Up have been raising awareness of the consequences of the mass drugging policies and the need for more humane and effective alternatives.

One woman, labeled bipolar and heavily drugged, had been told by a psychiatrist that she would be a lifelong patient and should enter a group home. Instead, as that person wrote to ISEPP, the “patient” had stopped taking psychotropic drugs, started a family and entered a Ph.D. program with a chancellor’s fellowship. “Life is not a disorder,” she wrote.

Today, with Operation Speak Up, Ruby has plans to organize local groups, particularly where concentrations of veterans exist “so vets can talk among themselves, can express their deepest fears and concerns, and still be accepted by their group.”

Ruby reports that the military, pressured by drug company marketing, has turned to the quick fix of drugging its soldiers and veterans instead of finding real solutions to mental and emotional problems. Drugs, he said, are not a real solution because they create a population of veterans who are “zombied out.”

Ruby calls the first-line policy of drugging veterans “short-sighted”—a policy he and Operation Speak Up intend to change.