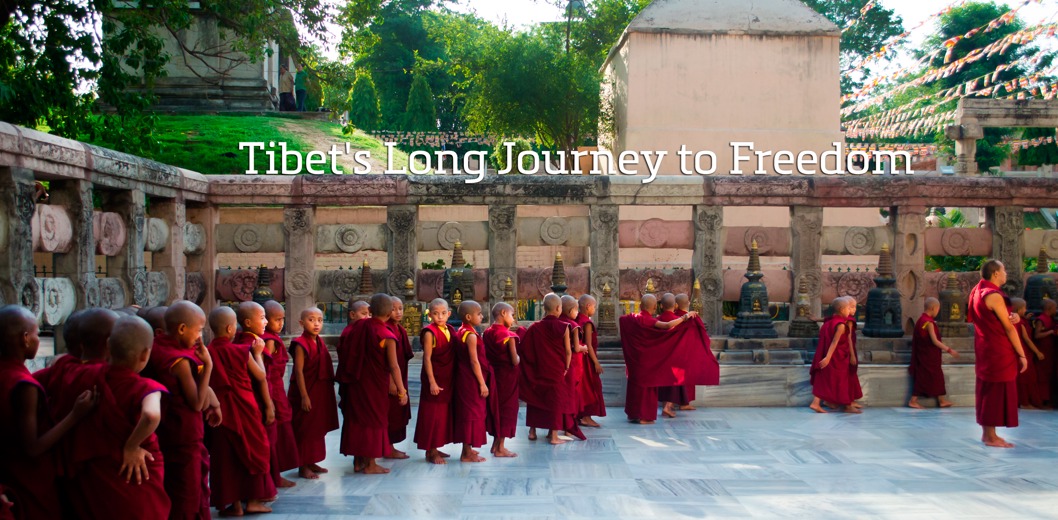

Tibet’s Long Journey to Freedom

It has been likened to a Shangri-La, a nation cradled in the clouds and snowy peaks of the Himalayas, rich in natural resources and steeped in a centuries-old culture dominated by spirituality.

It has also been described as hell on Earth, a land where, for the last six decades, its peoples have suffered a merciless repression that human rights organizations have described as cultural and religious genocide.

Today, Tibet is a nation struggling for freedom, with its strongest advocates of human rights living in exile. Despite crushing oppression, Tibetans have refused to relinquish their rights to nationhood, their cultural identity or the free practice of their religion.

Tibetan influence spread throughout Asia and China until the 19th century, with spiritual authority vested in the Dalai Lama, the highest religious authority in Tibetan Buddhism. A continuous succession of Dalai Lamas has held the position since the late 1500s.

A firmly established religious leader who held the steadfast loyalty of Buddhists throughout Tibet, and whose word was law among followers, the Dalai Lama was a force to be reckoned with by outside interests.

The Tibetan Plateau, known as the “roof of the world,” is the highest region on Earth with an average elevation of 14,800 feet. Tibet’s cultural and religious traditions date back millennia.

In an effort to strengthen its weakening grip on the country, Qing military forces from China ousted the 13th Dalai Lama in 1910, forcing him to flee to British-ruled India.

But the Qing regime’s hold on Tibet didn’t last. In 1912, a revolution toppled the dynasty, and in 1913 the Dalai Lama returned as ruler of an independent Tibet, an independence that, sadly, would not long stand.

In 1951, Tibet was overtaken by the People’s Republic of China, again forcing the Dalai Lama into exile. Next came Mao’s Great Leap Forward, which sought to eradicate all forms of religion. Hundreds of thousands of Tibetans were exterminated in an effort to erase the practice of Tibetan Buddhism. Approximately 6,000 monasteries were destroyed, including many of the religion’s most sacred sites. Protesters were either shot on sight or held as political prisoners and tortured mercilessly, sometimes for years on end.

Despite the unrelenting repression, Tibetan citizens continued to demand the return of their citizenship and human rights through a campaign of passive resistance, a hallmark of their faith. Some demonstrated peacefully, only to be met with arrest or bullets. Outraged human rights organizations later described the assault as “cultural genocide.”

Lhasa, the nation’s second most populous city, is home to the oldest and most sacred temples of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Venerable Tenzin Bagdro, a man who would eventually become one of Tibet’s most outspoken advocates of religious freedom and human rights, was 13 when he first witnessed the suppression of his people.

“I experienced the Cultural Revolution,” he said. “I saw monks being disrobed and brutally beaten when they voiced their opinions. Thousands of old scriptures were burnt; many monasteries were destroyed. Around the time I was admitted to a Chinese school, we were denied the study of our own language and traditions.”

Repression fueled a burning desire in Bagdro to fight for freedom. In 1985, he became a Buddhist monk. Three years later, in the city of Lhasa, during one of the most important religious festivals in Tibet, he helped to lead a protest against the repression.

Knowing military authorities would likely seize him, Bagdro made a promise to himself: “If I am caught, I won’t give the Chinese the names of any of my co-conspirators.”

The day of the protest, Chinese troops fired randomly into the crowd. A 13-year-old girl was struck in the chest and died in front of him. Fellow monks were thrown from terraces of surrounding buildings and left bleeding and broken in the streets.

“Jokhang Temple in Lhasa is one of the holiest. That day it was covered in blood,” Bagdro said.

Tibet contains some of the richest mineral deposits on the planet, including copper, iron, lithium, gold, oil and uranium, estimated at more than $128 billion.

Arrested a month later, Bagdro was incarcerated for three years. Hell would have been easier to live through.

“Every day I was beaten,” Bagdro said. “They put an electric baton on my neck, in my ears and in my mouth. I was asked to kneel down on crushed glass while they put a hot iron on my feet. During the night, they tied me upside down. The female prisoners were being raped repeatedly by the prison policemen every night.”

When he was released after three terrible years, his promise not to reveal the names of his friends was unbroken.

Freedom led Bagdro to Dharamshala, India, and a special audience with His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama, a preeminent advocate for human rights in Tibet and throughout the world. For Bagdro, the meeting rekindled his purpose to fight for a free Tibet. And so his voice joined a chorus of Tibetan expatriates working toward that goal.

Following the 1959 invasion that began Bagdro’s harrowing journey, the Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile in Dharamshala. Buddhist monasteries razed in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution were rebuilt in their new home to educate new generations of Buddhist monks and nuns to preserve the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism.

In approximately 640 AD, under the rule of Songtsan Gampo, Buddhism was established in Tibet. During the next two centuries, the religion became a dominant force throughout Central Asia, and has remained part of the spiritual life of the culture to this day.

The keeping of Tibetan cultural traditions—which were being systematically eradicated by the Chinese—was equally important, and depended on a generation of children separated from their families or orphaned by decades of violence.

From 1964 to 2006, Jetsun Pema, sister of the Dalai Lama, presided over the Tibetan Children’s Villages (TCV), a thriving, integrated educational community for destitute children in exile, with the purpose “to ensure all Tibetan children under its care receive a sound education, a firm cultural identity and become self-reliant and contributing members of the Tibetan community and the world at large.”

And so Tibet began to gradually rebuild its cultural identity and focus world attention on the need for human rights reforms. That effort continues to this day and is in keeping with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948, the first and most expansive expression of the universal and inherent rights of every person.

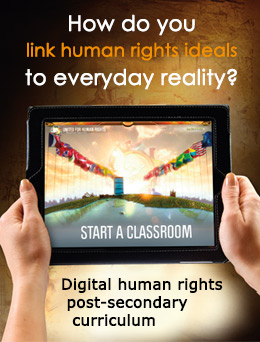

Youth for Human Rights International (YHRI), a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization, promotes the Declaration with a program that educates people and governments around the world on the rights it guarantees.

Fiorella Cerchiara and Annalisa Tosoni of the Association for Human Rights and Tolerance of Italy, an affiliate of YHRI, presented a copy of the group’s publication What Are Human Rights? to Tibetan community leader in exile Yakar Gelek.

“We dreamed one day we would have a United Tibet project,” said Gelek. “That day has come. This is the peace project we have been looking for. We must bring this project to all members of our community, the Tibetans in exile, so we guarantee our future as a culture.”

In May 2010, Jetsun Pema was honored by the Association for Human Rights and Tolerance at an event in Milan for her role in establishing the Tibetan Children’s Villages and her 42-year dedication to saving refugee children. She went on to implement a Youth for Human Rights International educational program in Tibetan schools and monasteries throughout India.

In 2013, the Venerable Tenzin Bagdro was invited to Italy to receive special recognition for his work to advance the cause of human rights, where he was introduced to the Youth for Human Rights program and educational materials. Bagdro saw how the materials could be used to educate future generations on the importance of their human rights.

“There are two aspects to the program,” Cerchiara explained. “Educating Tibet’s future generation included giving them a complete understanding of exactly what those rights [spelled out in the Universal Declaration] are so they can become advocates for protecting those freedoms.

“But not only the children needed to be educated, so did many of those who had been working for years to protect human rights. One man came to me in surprise and said, ‘I’ve been fighting for human rights for decades, but I never really understood exactly what those rights were!’”

From this grew United for Tibet, a project dedicated to protecting the cause of human rights through education. In 2014, lectures and 5,000 copies of What Are Human Rights? were presented to monks of the Golden Temple, the largest Tibetan Buddhist monastery in India. Two hundred copies of the educator’s guide were presented to teachers in the Tibetan Children’s Villages to educate young people on their fundamental human rights.

As a result, Yakar Gelek, Annalisa Tosoni and Fiorella Cerchiara drafted a plan to translate into Tibetan all the materials of the campaign, including teacher lesson plans, workbooks and audiovisual material, so the entire program could be implemented throughout the Tibetan community of India.

But before such a massive plan could be fully implemented, it required an approval from His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. And so the materials were brought to Tibet’s spiritual leader, who not only approved the plan, but included his personal prayer to be printed in the front of all translated versions of What Are Human Rights?

“The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a monumental document of the United Nations that establishes the fundamental equality and rights of all people on this planet, irrespective of their race, color, creed, or whether they are believers or not. We should all show due respect to this declaration and abide by its provisions.

“I am grateful and happy that the Association for Human Rights and Tolerance has arranged to translate this important document into Tibetan and is now also publishing it in book form to distribute it among Tibetan youth.

“With prayers,

“Dalai Lama”

“The battle is far from being won,” says Cerchiara. “But now those fighting for the cause have a tool that can be used to make the importance of human rights real to others.”