The Fight to Know

It’s probably not the best idea to pick fights with the FBI—or the CIA, or the National Security Agency, or the Department of Defense. Yet historian and animal rights activist Ryan Shapiro has been at war with all these federal agencies for years—and he says he’s just getting started.

A Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Shapiro is the “most prolific” requester of records from the FBI under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), according to the Department of Justice (DOJ). With help from the National Lawyers Guild, a public interest association of lawyers, students and others, he has filed multiple lawsuits against the FBI, NSA, CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency. One of the court cases revolves around Shapiro’s attempt to obtain every possible document pertaining to U.S. spying on the late South African leader Nelson Mandela and the anti-apartheid movement he led.

Last year, Shapiro and an investigative journalist, Jason Leopold, sued the CIA for its failure to comply with their FOIA request for records about the agency’s alleged spying on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and its review of the CIA’s infamous post-9/11 program of rendition, detention and torture-induced interrogation of terrorism suspects.

Since Shapiro began requesting a significant number of records from the FBI under FOIA in 2010 (his first requests date back to 2004), the agency has turned over more than 40,000 pages of records about its monitoring of the animal rights movement in the U.S. These are documents the agency initially said it did not have, says Shapiro, adding that the only reason the FBI parted with the records was a discovery he made while researching the agency’s internal regulations and court documents describing how it conducts FOIA searches. Shapiro found that when he requested documents about his fellow animal rights activists and got them to sign privacy waivers, the FBI almost always released information about them.

Through much of 2011, about four years after he began his Ph.D. dissertation on disputes over animals and national security from 1899-1979, Shapiro petitioned the FBI at least twice a day on average. Also in 2011, Shapiro sued the FBI in a federal district in Washington, D.C., for “obstinately refusing to process” 70 of his FOIA requests over several years.

In a secret, on-camera deposition to the court in 2012, a redacted version of which was given to Shapiro’s attorney, FBI Counterterrorism Division Deputy Assistant Director Michael Clancy asked for an Open America stay until September 30, 2019, which would allow the agency to process the “entire collection of documents” Shapiro had requested.

Open America refers to a Watergate-era appeals court ruling that allows agencies a stay on proceedings if they can show they are “deluged with a volume of requests for information” under FOIA and are therefore unable to meet the statutory limit of 20 business days for a preliminary response. The court granted the FBI the seven-year stay. Shapiro is contesting the decision.

In court, the FBI also invoked the “mosaic theory,” a Cold War-era legal argument used often by the administration of former President George W. Bush. According to this theory, Shapiro’s requests for documents, the agency contended, cannot be made public without posing a potential threat to national security. Shrewd enemies, the FBI’s reasoning goes, can string together bits of disparate and seemingly innocuous information into more intelligible wholes, or mosaics. (An FBI spokesman told Freedom he’s not permitted to comment on the matter because it’s under litigation.)

In the eyes of the FBI, says Shapiro, animal activists are potential terrorists. In fact, some of them, including Shapiro, have been prosecuted for running an animal rights website and trespassing on farms where they conducted undercover investigations during which they videotaped and “rescued” animals. (In 2004, Shapiro and a fellow activist faced felony burglary charges, which were reduced to a misdemeanor following a plea agreement.) The FBI routinely employs counterterrorism resources against this loose network of animal rights activists—“despite a lack of evidence that the groups are engaging in or supporting violent action,” the American Civil Liberties Union reported in 2005 after reviewing FBI documents obtained through FOIA requests.

“It’s had a deeply chilling effect on the animal rights movement,” Shapiro says of the FBI’s methods. Shapiro started his doctoral research in 2007 in an attempt to understand “how the animal rights movement went from being no threat at all before 9/11 to the leading threat.” He adds: “Just asking questions about the FBI’s handling of the animal rights movement is now understood as a security threat.”

Shapiro’s attempt to penetrate the FBI’s wall of secrecy highlights the struggles of obtaining government documents nearly half a century after Congress passed the Freedom of Information Act on June 20, 1966. Since it became effective on July 4, 1967, FOIA has given citizens, journalists and public interest groups the right to freely examine government information about everything from public health and the environment to maladministration and political corruption. (States have their own FOIA laws.) Despite substantive reform of FOIA in 1974, following the Watergate scandal, a great deal of government information is still protected by nine exemptions (and three exclusions) covering national security, privacy, trade secrets, confidential commercial and financial information, and some law enforcement records. Officials are required to offer explicit justifications, within specific parameters, for blocking access.

Perhaps because it’s the nation’s first and only law that requires federal officials to respond in a systematic way to citizens’ requests for federal records, advocates of open government in Congress try every few years to reform FOIA by ironing out its many loopholes. Since February, two separate but fairly similar bipartisan bills to amend FOIA, known as the FOIA Improvement Act, have been making their way through the Senate and the House. Both are aimed at establishing a statutory “presumption of openness,” first emphasized by former Attorney General Janet Reno in 1993 as a standard for dealing with FOIA requests. The principle would help ensure that government information may be withheld only if agencies can show that it’s too sensitive for public consumption.

Transparency advocates have been monitoring the bills with a sense of cautious optimism following the dramatic failure in the House of Representatives of an almost identical FOIA reform bill in December 2014, close on the heels of its successful passage in the Senate. Several legislators were quoted in the media complaining that they came under pressure from the government’s executive branch as well as banking and finance lobbyists to kill the reform effort. One observer described the bill’s 11th-hour demise, on the very last day of a two-year congressional session, as the House’s “victory over its own stated goals,” not to mention “a stinging defeat for more than 70 transparency organizations and government watchdog groups that lined up behind the act.”

There’s hope this time around, however, that the bill will eventually become law. Congress began another two-year session in January, and the bipartisan bills were introduced very early on, unlike in the previous session. “Those in favor of secrecy will have a much harder time running out the clock,” says Nate Jones, director of the National Security Archive, a respected transparency watchdog at George Washington University.

Still, matters aren’t moving as rapidly as some transparency activists would like. “We’re a little frustrated that after a big flurry of initial activity, things seem to have stalled in both the chambers,” says Patrice McDermott, executive director of Open the Government, a Washington-based nonprofit coalition of journalists, environmentalists, and library and consumer groups devoted to limited and less secretive government. “There was a good hearing in the House, but things don’t seem to be moving much there.”

House representatives are meeting behind the scenes, however, according to Jones, to discuss a host of measures that their bill shares with the Senate legislation. There are three measures in both bills that FOIA advocates find particularly heartening. The first aims to reform an often-abused provision called Exemption 5, a deliberative process privilege that permits the withholding of any “interagency or intra-agency communication.”

The second measure contains a Sunset provision that forbids agencies from using Exemption 5 as a reason to withhold information older than 25 years. (If this provision becomes law, Americans might finally become privy to details about the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba by the CIA, which is withholding a 30-year-old volume of the offensive’s official history from the public under Exemption 5, even though four preceding volumes have been released without any harm to national security.)

The third reform measure would give greater independence and authority to the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), an ombudsman created by Congress in 2007 to review FOIA policies and procedures as well as the compliance of federal agencies with the act. But because OGIS ultimately reports to the White House, like the rest of the executive branch, it’s not considered to be an impartial mediator in FOIA disputes. If the pending legislation in Congress becomes law, OGIS would be required to submit an annual report outlining its oversight of agency FOIA practices directly to Congress—without review or appraisal from any other government entity, including DOJ. Further, OGIS would be required to hold a public meeting on these annual reports once a year.

Many activists were disappointed that Congress didn’t push through the bill during the 10th annual Sunshine Week, a nationwide celebration of open government and freedom that kicked off March 15. Instead, in an odd move that cast a negative spotlight on the government, the White House announced on March 16—National Freedom of Information Day—that its Office of Administration would no longer be subject to FOIA. The decision solidified a policy under both Presidents Bush and Obama to reject requests to the office for records, which is responsible for record-keeping duties such as the archiving of emails, and was the only part of the White House answerable to FOIA.

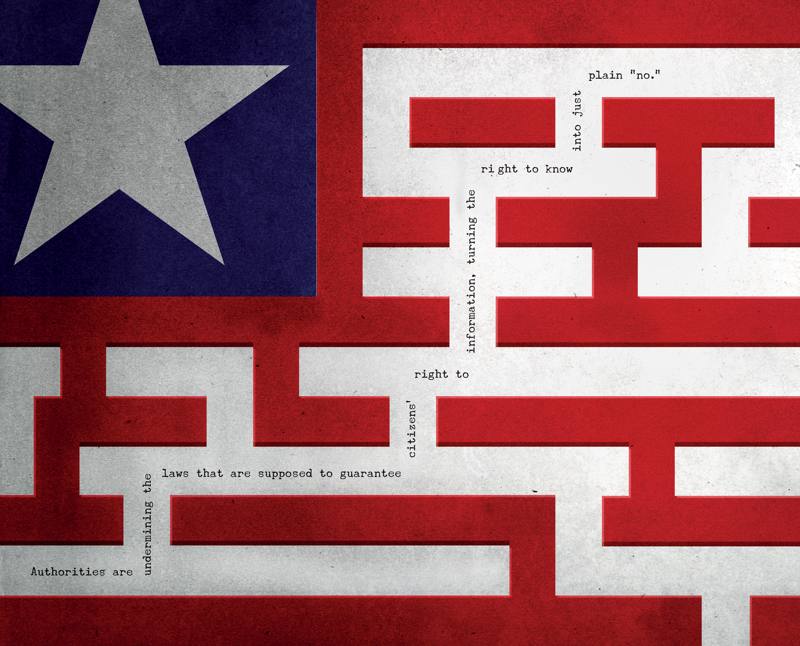

The announcement’s timing couldn’t have been worse. “It’s getting harder and more expensive to use public records to hold government officials accountable,” wrote Gary Pruitt, president and CEO of the Associated Press, in an article on the eve of Sunshine Week. “Authorities are undermining the laws that are supposed to guarantee citizens’ right to information, turning the right to know into just plain ‘no.’”

For their part, many activists are upset with President Obama because he came into office promising “an unprecedented level of openness in government.” His administration, wrote Obama in a memorandum to the heads of federal departments and agencies a day after his inauguration on January 21, 2009, “stands on the side not of those who seek to withhold information, but those who seek to make it known.”

According to the government’s FOIA website, requests for information have increased from 557,825 in fiscal 2009 to 704,394 in fiscal 2013—a 26 percent growth that roughly corresponds with Obama’s first term in office. Further, in 35 percent of the requests during that period, federal agencies released information in full to requesters. Partial information was disclosed in 30 percent of the cases, and just 6.1 percent of the requests were fully denied on the basis of FOIA exemptions.

But the percentage of fully granted FOIA applications remained lower during Obama’s first term than in all but one of the eight years of the Bush Presidency, according to Jason Ross Arnold, a political science professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. Obama’s reinstitutionalization of the Clinton-era “presumption of openness” standard, “after being pushed aside by Bush-Cheney, signaled that he and his administration would take that national commitment seriously,” writes Arnold in his masterly 2014 book, Secrecy in the Sunshine Era: The Promise and Failures of U.S. Open Government Laws. But the Obama Administration’s “record on FOIA and unclassified information disclosure more generally was mixed at best.”

Where Obama gets high marks on FOIA is in his revival of the government’s programs to declassify information, which former President Bill Clinton initiated in 1993 and which Bush abandoned a decade later. Classification decisions dropped from slightly more than 250,000, when Bush came to power, to about 60,000 in 2013, according to the Information Security Oversight Office.

Whether or not the criticism of Obama is unduly harsh, it’s safe to say that overall his rhetoric of transparency hasn’t kept pace with reality. As Jones of the National Security Archive puts it: “His biggest failure is that he has no one high up in the White House who goes from agency to agency, making sure that they’re following his instructions on transparency and FOIA.”

Still, one big difference between the Obama and Bush Administrations is that “under Bush there was no presumption of openness,” says Elizabeth Hempowicz, a public policy associate at the Project on Government Oversight, an independent Washington-based watchdog on government reforms. So is the attitude of agencies toward FOIA slowly changing? “Their frame of reference now is to figure out what they’re doing with more openness—to protect what they need to protect but not to hide illegality or abuse,” says Open the Government’s McDermott.

Another sore subject among activists looking to modernize FOIA centers on a loophole that allows government agencies to charge requesters exorbitant “search and review” fees even after an agency has missed, by months or years, the statutory 20-day deadline to respond. That this is in violation of the 2007 Open Government Act is only part of the problem. “The larger issue is that reporters, scientists and people at universities almost never pay fees—or pay very little,” says Jones of the National Security Archive. “Besides, fees only cover one percent of FOIA processing costs, and the only reason they exist is to deter requesters.”

Making a FOIA request isn’t difficult; making a successful FOIA request is the hard part. Because each federal agency processes requests independently, the first step is to write a letter to a particular agency. Some agencies provide sample letters on their websites. While you do not have to say why you need what you’re requesting—or offer evidence as to why the information you’re seeking needs to see the light of day—it’s a good idea to provide as much detail about the record as possible.

It’s also worth noting that under FOIA, any part of a document that is withheld must clearly show where the redaction occurs as well as how much material is missing (unless the missing information itself falls under a FOIA exemption). If a FOIA request is denied, the agency concerned must provide a signed letter stating the reason for the request’s denial. Finally, you have 60 days to appeal a denial in writing to the head of the agency or department. All denials can be contested in a federal district court—and the law requires the government to pay legal fees and court expenses if the case is decided in your favor.

Although courts are known to be typically deferential to federal lawyers, the judiciary holds the key to genuine FOIA reform. “The trick is to keep pressing the courts to interpret the act in the way that Congress intended, which is with a presumption of openness,” says Morton H. Halperin, a former deputy assistant Secretary of Defense.

Currently a senior adviser at the Open Society Policy Center, a Washington-based advocacy group aimed at influencing U.S. government policy on a range of domestic and international issues, including transparency and accountability, Halperin is among a growing number of activists who recommend that the government adopt a “public interest balancing test” that would allow courts, rather than federal agencies, to decide the importance of government information. The idea is to consider how the public might benefit from the disclosure of a particular piece of information, which would then act as counterweight to the government’s privilege claims.

As it happens, a public interest balancing requirement was part of the original Senate bill proposed in 2014. “But as the bill proceeded in the Senate, the public interest portion of it was taken out,” says David Sobel, a longtime FOIA litigation expert who is a Washington-based senior counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco nonprofit watchdog on issues related to freedom of information, expression and user privacy.

“There was a lot of pushback from the administration, and this year, when the bill was reenacted, the public interest balancing test provision was never on the table,” says Sobel. “Apparently, the White House had made clear to the relevant members of Congress that such an amendment would be a non-starter from the administration’s viewpoint.”

Over the decades, some of the most hawkish American leaders have conceded that the nation’s security depends not only on secrecy, surveillance and strategic warfare, but also on the free exchange of ideas in an informed society. “Such a citizenry is impossible without broad public access to information about the operations of government,” says prolific FBI requester Shapiro, adding: “As broken as FOIA is, the notion that the records of government are the property of the people, and that all we need to do to get them is to ask, is radically democratic.”

Ajay Singh has written for a variety of magazines, including Time, The American Spectator and The Independent on Sunday. A former Associated Press correspondent, Ajay began his journalism career at the Wall Street Journal Asia in India. He is the author of Give ’Em Hell, Hari, a 1998 East-West postcolonial novel.